Rather than dwelling on this specific circumstance though, most of the narrative concerns a violent tragedy that befalls two other local families. I had to find an explanation other than the real one, which was that we were no more immune to misfortune than anybody else. Between the way things used to be and the way they were now was a void that couldn’t be crossed. And mistakes ought to be rectified, only this one couldn’t be. couldn’t understand how it had happened to us. The narrator of the story loses his mother in the same way and suffers the same sort of shock:

I put the people back, I put the places back. I couldn’t do it literally, but I could put it in the pages of a book. I felt the need to put things back the way they were before. In this semi-autobiographical short novel, his survivor guilt is somewhat displaced, but he very much tries to re-establish the childhood world, in Lincoln, IL, that his loss ended:

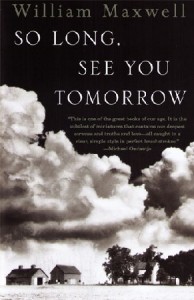

The beloved long-time New Yorker editor, William Maxwell, was two years younger than Grandpa and he lost his mother in the epidemic when he was ten years old, a loss which, likewise, haunted him his whole life. He, of course, would never talk about this, but it did seem to scar him permanently. He lost his two brothers in the Great Influenza, From what I understand, in one instance he came home from school not even realizing a brother was ill and he had already passed. There was a component of this reserve though that I never really understood until the past year: survivor guilt. You never doubted his love, but you couldn't expect it to be demonstrative. And, as one would anticipate, was emotionally reserved. He never swore in his life, didn't drink, didn't smoke, worked Saturdays and kept sabbath on Sundays. The man used garters to hold up his socks. He was so proper you almost never saw him out of a suit. The Grandfather Judd was the WASPiest man you could ever hope to meet.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)